This blog post is chockablock with information. Here is what you will find inside: I put the Winslet’s Tracy Tank through five muslin test versions to get the fit right, and uncovered a pattern with sizing inconsistencies, missing binding measurements, confusing ease allowances, and a few details that made me wonder if the company is connected to some kind of AI pattern generated content farm. You will get the exact alterations I made to each pattern piece, the math behind my 85% binding stretch ratio, details about the knits I used, attachment methods that avoid scratchy edges, and a deep dive into sports bra biomechanics research that explains why racerback straps put more pressure on shoulders than vertical ones. Read to the end if you want to know why researchers use toupee tape in sports bra studies and why someone had to come up with the term “breast slap”.

The Humble Tank Top

Tank tops and I have a complicated relationship. My shoulders, bust, and waist land in three totally different sizes, which makes fit a challenge. I’ve had a bit more success with men’s patterns, but what I want is a women’s tank pattern that actually fits my body. My checklist looks like this:

- NO racerback styles (see the aside at the end of the post; quick version, there’s solid research suggesting bra straps that angle toward the neck are a bad idea)

- Shoulder seams wide enough to fully cover bra straps

- No gapping around the armhole

- High enough under the arm so my sports bra doesn’t show

- Neckline can be high or low—I’m flexible there

- Not tight below the bust, but also not super flowy—just skimming the body

- Hip-length

Loose workout tanks look cute, but the moment you try doing side planks while sweaty, it is game over. I need a tank that moves with me, not one that twists up like a wet rag.

The blue Nike tank comes close. They added a panel under the arm at the bust level to get better shaping. Smart idea. I still want a wider shoulder though. Let me have full bra strap coverage.

This is what happens without shaping: floppy, low underarms and no structure. The expression on the model’s face says it all.

If you try to fix the fit by tightening everything, you end up with gapping at the front armhole and pooling at the back. Not for me.

I am also not into tanks where the center front swings away from the body. A clean, body-skimming silhouette is hard to achieve, but that is the goal.

I know what I want, but how am I going to achieve it? To get the kind of shaping I need, you either add a bunch of darts, or you break the pattern into multiple panels so the seam lines do the shaping for you. When you sew panels together, those seams act like darts. They add contour and fit without having to fold out extra fabric. It’s a more complex construction method, but it’s the only way to get a close, comfortable fit across curves without ending up with gaping armholes, pulling at the bust, or fabric pooling at the waist. But what pattern to use?

The problem is that there are not many patterns out there. It is a surprisingly empty part of the market. Here is what I found:

I was most curious about the Winslet’s Tracy Tank, but the company itself raised questions. Some samples look great, others look like no one ever checked the fit. It felt like a gamble, but I figured why not try it. The size range at least was decent.

Analyzing Style and Fit

The Tracy Tank has a relaxed fit with a high neckline and uses a front piece, back piece, upper and lower side panels, and a back yoke. The multi-panel design makes a closer fit possible without darts.

I’ll talk more about this in the alterations section, but my one issue with this pattern is that it doesn’t provide any binding length measurements. The instructions just say, “Attach with a binding attachment!” Not everyone has one (or wants one), so that’s not super helpful. If you attach your binding at a 1:1 ratio with the armhole or neckline, you’ll end up like the woman wearing the Hoka tank above—disappointed and unamused. I found that using 85% stretch worked best for me, but the attachment method also mattered too. Here’s how I calculated length:

- For example, my armhole circumference is 22 inches and 85% of that is 18.7 inches

- I added seam allowance: 3/8 inch on each side, so 0.75 inches total

- Final elastic length is 19.45 inches but I rounded up to 19.5 inches

Sizing

Picking a Size

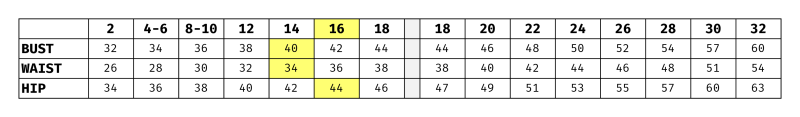

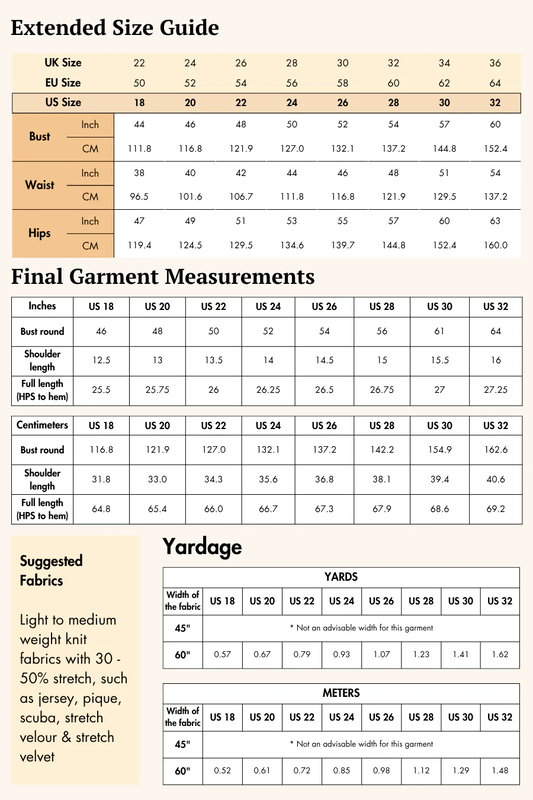

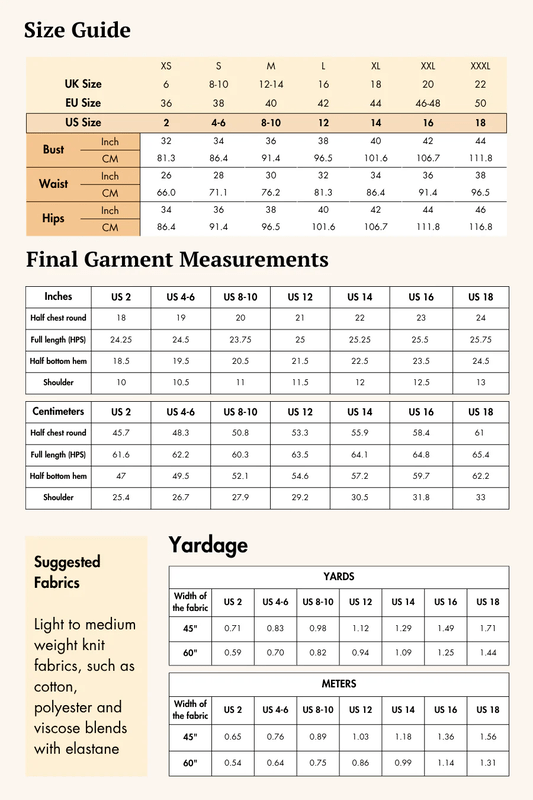

The pattern comes in two ranges. The regular range has busts from 32 to 44 inches, waists from 26 to 38, and hips from 34 to 46. The extended sizes go from 44 to 60 at the bust, 38 to 54 at the waist, and 47 to 63 at the hip. There is no guidance on how or where to measure, or what makes the extended range different from the regular one. Not a great start.

I currently measure 39-inch bust, 33-inch waist, and 42-inch hip (43 inches if using a measuring band). However, I’ve mentioned a few times in the past that I need to pick a size based on my high bust measurement, which more accurately represents my larger frame.

In a typical body form, your high bust should be smaller than your full bust, and the difference between your full bust and high bust measurement would tell you your cup size:

- 1 inch = A cup

- 2 inches = B cup

- 3 inches = C cup

- 4 inches = D cup

- 5 inches = E cup (or DD)

- 6 inches = F cup (or DDD)

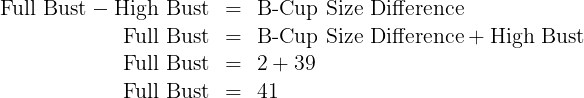

However, my high bust and full bust are both 39 inches, and I don’t have less than A cups. So if I take my high bust and reverse-engineer the “expected” full bust measurement (since most patterns are drafted for a B cup, meaning a 2-inch difference), I’ll be able to pick my size that fits my frame:

Based on my full bust alone, I fall between a size 12 and 14. Based on the “calculated” full bust and my hip measurement, I’m between size 14 and 16. I ended up choosing a size 16, since it accounts for my larger frame and should give me enough room at the hips.

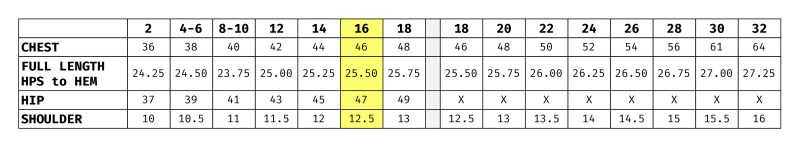

Final Garment Table

The pattern did, thankfully, include a final garment measurement table. However, the extended size range didn’t include any information about hip circumference. Because that information was missing, I measured the pattern pieces myself. That kind of omission is a red flag.

For the chest, I measured across the bottom of the armhole parallel to the floor. For the regular size range, my measurements matched the final garment table exactly. But for the extended size range, I was nowhere close. My measurements were 4 inches larger for sizes 18 through 28, and 2 inches larger for sizes 30 and 32.

For the hip, I measured across the bottom hem. Again, my numbers matched what was listed for the regular size range. But for the extended range, there were no listed values, so I have no way to verify if my numbers are correct.

Based on these measurements, the pattern has 4 inches of positive ease at the chest in the regular size range and 6 inches of positive ease in the extended range. For the hips, there’s 3 inches of ease in the regular range and 4 inches in the extended. Why so much ease at the chest?

There were other oddities in the final garment table. It took me quite a while to figure out what shoulder measurement they meant. Eventually, I think I figured it out. For the regular sizes, I was able to replicate the measurement by going from outside shoulder to outside shoulder on the back pieces. But using that same method on the extended size range gave me results that were 1.5 inches larger than what the chart said.

In the end, there are quite a few inconsistencies in the size chart and final garment measurements. The pattern doesn’t include any guidance on how the extended size range differs from the regular range. There’s also no explanation of where or how to measure your body when choosing a size. And it would be really helpful to know the intended fit of the garment since the pattern has more ease at the chest and less at the hips, which feels counterintuitive for an athletic tank top. All the examples I showed at the beginning (minus the Hoka) have a tighter fit at the bust. You’ll get better range of motion the closer the garment sits to your body and that’s the point of athletic styles, full range of motion.

My spidey senses were already tingling just from looking at the website and product images, it felt like this pattern company might be a content mill cranking out AI-generated patterns without careful drafting. These sizing issues haven’t done much to ease that suspicion.

Materials

I made two tank tops using two different fabrics from Blue Moon Fabrics.

The first is Allure Polyester Spandex with Wicking. I need fabric that can handle a lot of sweat, and this one delivered. According to their site:

“Allure is a 4-way stretch polyester spandex double knit with wicking properties; ideal for high performance active wear. Its lightweight composition and temperature-regulating capabilities make it ideal for fabricating a variety of compression and base-layer apparel, ensuring you stay comfortable and dry no matter the activity. Allure is designed to give you the most comfortable experience possible, with fabric that moves with you and maintains breathability and moisture management. Its quick-drying capabilities make it easy and convenient to wash and wear.”

The fabric content is 82% polyester, 18% spandex with a weight of 230 gsm. It has 4-way stretch and comes in 42 colors. I’m in love with this fabric. It actually gets softer and more comfortable the more you sweat in it. The drape of the fabric is flowy and soft.

The second fabric I tested is Harmony Ultra Soft Nylon Spandex Double Knit. Like Allure, it’s technically a double knit, but I specifically wanted to try a nylon-based option instead of polyester. The description intrigued me:

“Harmony is a 4-way stretch Ultra Soft Nylon spandex double knit ideal for high performance active wear. Its lightweight composition and temperature-regulating capabilities make it ideal for fabricating a variety of compression and base-layer apparel, ensuring you stay comfortable and dry no matter the activity. Harmony is designed to give you the most comfortable experience possible, with fabric that moves with you and maintains breathability and moisture management. Its quick-drying capabilities make it easy and convenient to wash and wear.”

The fabric content is 69% nylon, 31% spandex, with a weight of 210 gsm. It’s available in 52 colors.

Release: 4/2012

This fabric immediately reminded me of my early 2010s Lululemon tops. Specifically, the Lululemon Chaturanga Tank, which was released in April 2012 and made from Luxtreme, also a 69/31 blend—just like Harmony. The fabric has a crispness to it and drapes more like linen than a soft spandex knit. That’s actually a plus here, since the top has a bit of billowiness that allows for airflow during workouts.

Subscribe to continue reading

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.